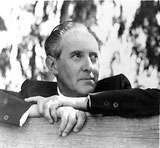

Norman Cohn: Life

Norman Cohn, a Fellow of the British Academy, is best known as the author of The Pursuit of the Millennium.

In this book, he related the apocalyptic beliefs of twentieth-century totalitarian movements, whether Nazi or Communist, to their origins in medieval heresy.

Published in 1957, the book remains in print. In 1995, the Times Literary Supplement included The Pursuit of the Millennium in its list of the 100 most influential books since 1945.

The account of Cohn's life included below is based on his obituary by William Lamont in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Other obituaries of Norman Cohn were published in The Guardian, The Telegraph, the New York Times and History Today.

Norman Rufus Colin Cohn (1915–2007) was born on 12 January 1915 at 41 Alleyn Park, Dulwich, London, the youngest of six sons of August Sylvester Cohn (1867/8–1947), barrister, and his wife, Daisy Annie, née Reimer (1872/3– 1951). His father was a German Jew who became a naturalized British citizen in the 1880s after hearing Gladstone expound liberalism. His mother was partly German, a Catholic, who spent most of her childhood in South Africa, where his father on holiday met and married her. His brothers and cousins fought on opposite sides in the First World War.

Cohn was educated at Gresham's School, and in 1933 won a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford, to read French. He graduated with a first-class degree in 1936, and uniquely at that time in the modern language school was awarded a further three years to read German. The outbreak of the Second World War prevented his pursuing immediate plans for graduate research, although his linguistic skills would be used to advantage in his war service and in the books he wrote after the war ended. He married on 3 September 1941 a Russian, Vera Broido (1907–2004). She and Cohn had one son, Nik (b. 1946). In the same month as their marriage Vera's mother was shot as a Menshevik traitor after solitary confinement in Russia since 1927, but only after the archives were opened following the collapse of the Soviet Union did she know of her mother's fate. Vera was a close friend of Frederic Voigt, the Berlin correspondent of the Manchester Guardian, and the thesis of his book Unto Caesar (1938), that communism and Nazism were both forms of secularized millenarianism, had made a great impression on her. It would be developed to great effect by her new husband.

Cohn volunteered for the army in 1940 and was commissioned in the Queen's Royal regiment; he was transferred to the intelligence corps in 1942, and from Bletchley at the end of the war was sent to Austria, where he listened to Nazi prisoners talking among themselves when they thought that their captors could not understand them. In peacetime he resumed his academic interests in languages between 1946 and 1962, first as a lecturer in French at Glasgow University and then as professor of French, first at Magee University College, Londonderry (1951–60), and then at King's College, University of Durham (1960–3).

It was as a professor of French that Cohn published his first major book, The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957), but in the ten years that it took him to write it he had turned himself into a historian. The book met with instant acclaim. His brilliant evocation of John of Leyden's reign of terror in Münster—and of the flagellants who seemed to have walked straight out of Ingmar Bergman's movie The Seventh Seal, released in that same year—stayed in the reader's mind. Cohn intended it to do so, but not at the price of failing to recognize that millenarian speculations could have stabilizing effects as well as destabilizing ones. He was particularly sensitive to the power of belief in the idea of a ‘last world emperor’ as a secular companion figure to that of the ‘angelic pope’. There are thirty-one entries on the emperor cult in The Pursuit of the Millennium index, which will only surprise those who accept a simplified reading of the Cohn thesis.

The book remained in print throughout Cohn's lifetime and was translated into French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Norwegian, Greek, Hebrew, and Japanese. The Times Literary Supplement in 1995 listed it among the 100 non-fiction works that had had the greatest influence on the way in which post-war Europeans perceived themselves. At the time it was published there was no systematic history of millenarianism into which a book could be slotted. Cohn's book went a long way to filling that gap. However, in its concluding chapter, he restated his still uncompleted mission to recover the historical roots of twentieth-century persecution and genocide.

In 1963 Cohn was appointed as director of the newly established Columbus Centre at the University of Sussex.

Its origins were to be found in April 1962 at a meeting held to commemorate the uprising of the Warsaw ghetto.

The editor and proprietor of The Observer, David Astor, gave an address that was printed in Encounter the following August. He argued that contemporaries were still far from grasping the full implications of the holocaust and called for an academic study of the processes that led up to it.

Astor's address provoked much interest between 1962 and 1963, which led to discussions in which the author of The Pursuit of the Millennium was invited to participate, and culminated in Astor's offering Cohn the directorship of the Columbus Centre in 1963. Although based at Sussex University, it was the trust set up by Astor, not the university, that paid Cohn's salary, and with it a small annual fee to the university. Its remit was research, not teaching, and a number of books were published under the centre's auspices bearing the imprint of the Sussex University Press, not least of them Cohn's own two publications for the centre.

The first, Warrant for Genocide (1967), established that the key document of a supposed Jewish world conspiracy, The Protocol of the Elders of Zion, was a nineteenth-century tsarist forgery. Cohn's book was translated into French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Serbian, Russian, Hebrew, and Japanese. In the Soviet Union the Russian translation circulated as samizdat before its open publication in 1990. In the United States the book gained the Anisfeld-Wolf award for its contribution to race relations. More than forty years after its original publication the English version is still in print.

His second publication for the centre, Europe's Inner Demons (1975), was translated into French, Spanish, Hungarian, Norwegian, and Japanese, and also remained in print at the time of Cohn's death. In it he showed how the idea of the satanic pact was at the heart of the European witch craze, and on the way put to rest the once influential thesis of Margaret Murray's The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) that witches really existed as a survival of an ancient pagan religion.

Cohn held the title of Astor-Wolfson professor of history at Sussex from 1973, and after his retirement in 1980 was made an emeritus professor. He was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1978. Within a year of retiring as director of the Columbus Centre he was invited to Concordia University, Montreal, to help to launch the Institute for Genocide Studies, which came into existence in 1985. He published two further books, Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come (1993) and Noah's Flood: the Genesis in Western Thought (1996).

His wife Vera predeceased him in 2004, having compiled her memoirs in her ninety-first year under the title Daughter of Revolution (1998). In December 2004 he married another remarkable Russian, Marina Voikhanskaya, a psychotherapist (and daughter of Israel Fridlender, scientist), who was forced to leave the Soviet Union in the 1970s after protesting against the compulsory detention of political dissidents in psychiatric hospitals.

Cohn died at his home in Cambridge, on 31 July 2007, and was survived by Marina and his son, Nik, a celebrated writer, one of whose books inspired the musical Saturday Night Fever.